Original Cartilage and Evidence of DNA Preserved in 75 Million-Year-Old Baby Dinosaur

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and North Carolina State University have found evidence of preserved fragments of proteins and apparent chromosomes within isolated cell-like microstructures in cartilage from a baby duckbilled dinosaur. The findings further support the idea that these original molecules can persist for tens of millions of years.

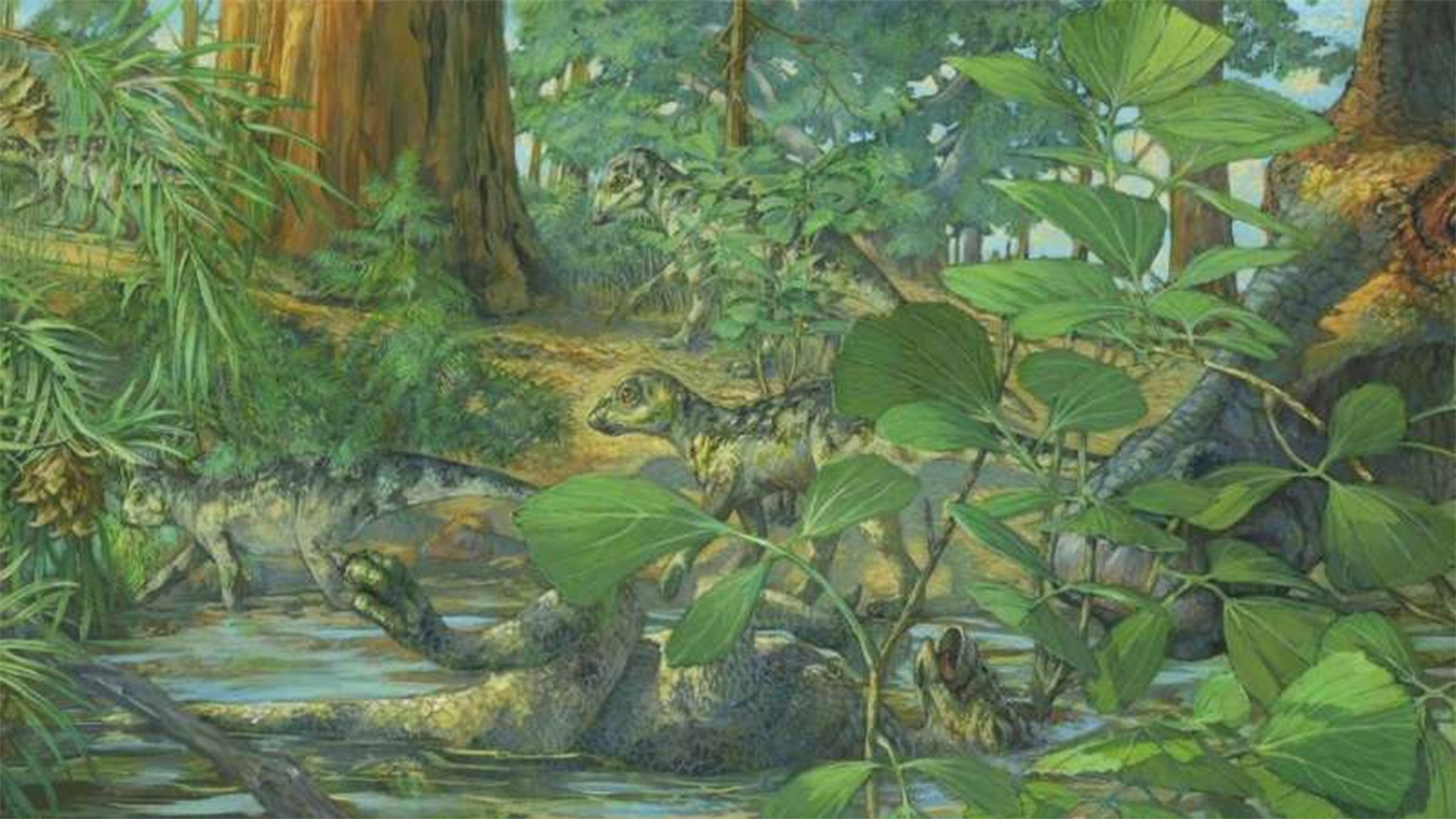

Microscopic analyses of skulls from a clutch of eggs, embryos,

hatchlings and nestlings belonging to Hypacrosaurus

– a type of duckbilled dinosaur that lived in what is now Montana during the

late Cretaceous period – were conducted by Alida Bailleul, a paleontologist

from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and corresponding author of a paper

describing the work. She noticed structures within certain tissues that were consistent

with chondrocytes, or cartilage cells, and within these were internal

structures resembling nuclei and chromosomes.

“The skull bones of baby dinosaurs are not fused when they

hatch, but instead, some of them have cartilaginous plates that fuse later as

bone forms in the spaces between them,” Bailleul says. “Seeing exquisitely

preserved microscopic structures that resembled the specific cell types found

only in cartilage, and which would have been present in the living organism in

these tissues, led us to hypothesize that cellular preservation may have extended

to the molecular level.”

Bailleul, at China’s Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and

Paleoanthropology, led an international team to determine whether these

original molecules had preserved over time. The team included Mary Schweitzer,

professor of biology at NC State with a joint appointment at the North Carolina

Museum of Sciences, as well as other researchers from Canada and the U.S.

The team performed immunological and histochemical analyses of tissues

from the 75-million-year-old hatchling skull, comparing the results to those

from an emu skull at a similar stage of development.

“Bird skulls ossify, or harden, in the same pattern as this

hadrosaur’s skull would have, and primitive birds (ratites) like emus are the

closest relatives we have alive today to non-avian dinosaurs,” Schweitzer says.

The cartilaginous tissues and chondrocytes from the dinosaur skull reacted with antibodies to collagen II, but the surrounding bone did not react with collagen II antibodies. This is significant because collagen II is found only in cartilage, while collagen I dominates in bone. Comparing the results to the emu confirmed the findings.

“These tests show how specific the antibodies are to each type

of protein, and support the presence of collagen II in these tissues,”

Schweitzer says. “Additionally, bacteria cannot produce collagen, which rules

out contamination as the source of the molecules.”

The researchers also tested the

microstructures for the presence of chemical markers consistent with DNA using

two complementary histochemical stains that bind to

DNA fragments within cells. These chemical markers reacted with isolated cartilaginous cells, supporting

the idea that some fragmentary DNA may remain within the cells.

“We used two different kinds of intercalating stains, one of which will only attach to DNA fragments in dead cells, and the other which binds to any DNA,” Schweitzer explains. “The stains show point reactivity, meaning they are binding to specific molecules within the microstructure and not smeared across the entire ‘cell’ as would be expected if they arose from bacterial contamination.”

“Although bone cells have previously been isolated from dinosaur bone, this is the first time that cartilage-producing cells have been isolated from a fossil,” Bailleul says. “It’s an exciting find that adds to the growing body of evidence that these tissues, cells and nuclear material can persist for millions – even tens of millions – of years.”

The work appears in National Science Review and is supported by the National Science Foundation, the Packard Foundation and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

-peake-

Note to editors:

An abstract follows.

“Evidence of proteins, chromosomes and chemical markers of DNA in exceptionally preserved dinosaur cartilage”

DOI: 10.1093/nsr/nwz206

Authors: Alida M. Bailleul, Chinese Academy of Sciences; Wenxia Zheng, Mary Schweitzer, North Carolina State University; John R. Horner, Chapman University; Brian Hall, Dalhousie University, Canada; Casey Holliday, University of Missouri

Published: National Science Review

Abstract:

A histological ground-section from a duck-billed dinosaur nestling(Hypacrosaurus stebingeri) revealed microstructures morphologically consistent with nuclei and chromosomes in cells within calcified cartilage. We hypothesized that this exceptional cellular preservation extended to the molecular level, and had molecular features in common with extant avian cartilage. Histochemical and immunological evidence supports in situ preservation of extracellular matrix components found in extant cartilage, including glycosaminoglycans and collagen type II. Furthermore, isolated Hypacrosaurus chondrocytes react positively with two DNA intercalating stains. Specific DNA staining is only observed inside the isolated cells, suggesting endogenous nuclear material survived fossilization. Our data support the preservation of calcified cartilage at the molecular level in Mesozoic material, and suggest that remnants of once-living chondrocytes, including their DNA, may preserve for millions of years.

This post was originally published in NC State News.