Chemistry Professor Sniffs Out Excellence

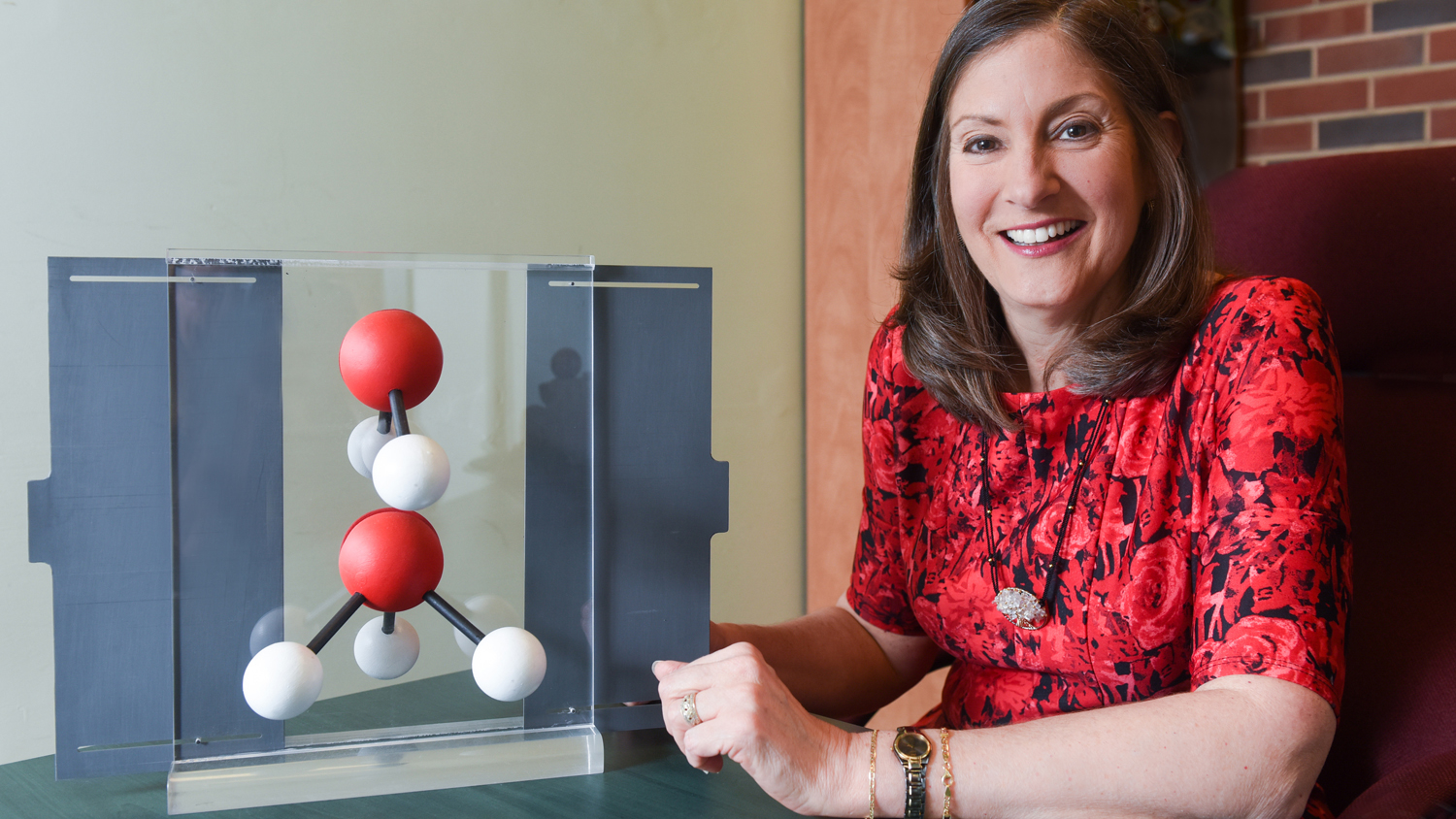

Maria T. Oliver-Hoyo, Alumni Distinguished Undergraduate Professor of Chemistry at NC State, is so fascinated by the teaching of chemistry that she has become a leading light in the study of chemistry education — and she’s so good at it that she was recently named a winner of the 2017 Excellence in Teaching Award from the UNC system Board of Governors.

It’s all the more ironic, then, that Oliver-Hoyo is not one of those seemingly charmed people who wind up doing something they’ve always wanted to do.

“Chemistry professor was not my first choice of career,” she says. “I love comparative literature, I love mathematics; I love everything. At first I couldn’t decide between the humanities and the sciences.”

When Oliver-Hoyo graduated high school and enrolled in the University of Puerto Rico, she learned that students there could take an exam to determine whether they’d be allowed to bypass the first year of general education courses and go straight into the college of sciences. Only the students who scored among the top 100 were selected for the accelerated program, so Oliver-Hoyo decided to take the exam and let the result guide her choice.

Her high exam score got her into the college of sciences, but then she faced another choice: Which science would she pursue?

“I loved math the most because it was easiest for me, so I thought, I don’t want to do that,” she recalls. “I didn’t like physics because I thought it was too dry. At the time, biology depended too much on memorization, so I didn’t want to do that either. Chemistry, though, was the most challenging field of all for me. I had to study very hard to grasp it. I had to learn how to study. So I said, that’s where I’m gonna go. I wanted that challenge.”

Oliver-Hoyo rose to the challenge, earning first her bachelor’s degree and then an M.S. from Georgetown. She wanted to pursue a chemistry Ph.D, but by then she was married to a member of the U.S. armed forces, and their frequent relocations prevented her from entering a doctoral program. Instead she taught chemistry as a lecturer or an adjunct professor at different institutions, and that’s when she became interested in the fact that people were somehow able to understand the sophisticated information she was trying to convey to them.

How did that process actually work? The question captivated her.

“I was driven to try to explain it,” she says.

That’s why, when her husband retired from the military, she entered a Ph.D. program in the nascent field of chemistry education research (CER), which studies how chemistry is taught and learned. In 1999, freshly minted doctorate in hand, Oliver-Hoyo came to NC State to develop a graduate program in CER.

“Any teacher will tell you that you can do the same thing in two different semesters, and it will work beautifully in one semester and not the other,” she says. “Why does that happen? I could have gone into any number of chemistry fields, including industry, but this is what interested me most: how to create more effective instruction.

“That’s what we do in CER.”

One of Oliver-Hoyo’s most notable innovations in CER is her “sensorial experiments,” which are based on her definition of chemistry.

“Chemistry is the science of studying stuff,” she says. “Everything you perceive through your five senses is what we study in chemistry.”

The problem with most undergraduate chemistry lab experiments is that they ignore four of the five senses and rely solely on visual input — the color change observed in a titration experiment, for instance. This works well enough for most students, but what about vision-impaired people, or the 8 percent of males and 0.6 percent of females who are color-blind? Those students usually either let someone else do the experiment for them or are discouraged from going into sciences that require experimentation, she says.

Oliver-Hoyo came up with a different solution — an innovation that utilizes another of the five senses: the sense of smell.

“We created an olfactory indicator,” she says. “When the chemical reaction takes place to let you know that your reagent and your solution have reached their stoichiometric amounts, instead of being demonstrated by a change in color, the reaction produces compounds that smell like onions and garlic. That’s how you know the titration has reached its endpoint and you can stop the experiment, make your calculations and present your findings.”

Oliver-Hoyo has also adapted the SCALE-UP model for use in chemistry classrooms. Developed by NC State physics professor Bob Beichner, SCALE-UP (Student-Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies) restructures large science classes by placing small groups of students at round tables and spending most class time on activities rather than lectures. Oliver-Hoyo’s adaptation required modifications both to the chemistry curriculum and the SCALE-UP model to account for the use of wet chemicals. Oliver-Hoyo has compiled more than 100 chemistry education activities suitable for use in a SCALE-UP classroom, all of which are freely available at the SCALE-UP website.

The common thread running through much of Oliver-Hoyo’s work is the visualization of chemical phenomena. Along those lines, her students are now using the 3-D printer in the D.H. Hill Library Makerspace to create physical models that will help them visualize the properties of macromolecules, such as DNA.

Oliver-Hoyo says she’s glad the UNC system is giving an award that honors achievements in the university’s primary mission: teaching students.

“Educating students is what we’re here for,” she says, “so I think an award that recognizes teaching efforts is very important. I’m appreciative of this award and humbled to have been chosen.”

This post was originally published in NC State News.